“…as an act of defiance as a way to care as a way to think differently as a capable future as a way to find out what’s in it for the forest…”

Extract from “What’s in it for the Forest? The Writing on the Wall”

– text exhibit by David Haley

.

When environmental change is happening at planet-wide scale, and in cumulative increments of time, we can be psychologically and culturally distanced from perceiving it “here” and “now”. This first group exhibition by the porously-constituted artist-researcher collective “PLACE” (People, Land, Art, Culture, Ecology) is a compelling effort to bring the meanings closer. Across more than thirty different works, the meanings are ecological, political, artistic and personal.

Artistically, this is an exuberant collection of diverse practices ranging from painting, sculpture, video and digital art to puppetry, textiles, narratives about science collaborations, embodied experiences, music and poetry. Everything is presented in a compact gallery space attached to the visitor centre at Grizedale Forest in Cumbria, where Forestry England and its institutional predecessors have promoted innovative engagement with contemporary art since 1968.

This compactness creates a kind of intensity, allowing the diversity to be taken in as a “choral” whole, and inviting an eye for conversational echoes and resonances between works that have been conceived and executed independently at a variety of times (some shown before; some newly-produced for this exhibition).

Here, one presumes, is a signal about the energy that develops from a collective of creatives with a shared purpose. Established by Harriet Fraser and Rob Fraser in 2021, in association with the Centre for National Parks and Protected Areas at the University of Cumbria, PLACE is a community of artists from within and beyond the UK who are engaged with issues of nature, environment and changing landscapes. Although this is the collective’s first physical exhibition, the group has been acting as a vibrant crucible of mutual exchange on agendas for research, advocacy and co-creation with other interests.

With a total of 32 artists featuring in See Here Now (see full list at end with links to bios – in text links are to blogs by artists for the exhibition), space here allows a mention only of a selected few.

In Tree Felling, multidisciplinary practitioner Jools Gilson has provided an audio track of a performed poetic reading that formed part of a project examining the clearance of an Irish old-growth forest to make way for a hydropower scheme in the 1950s. The original live performance (in 2023) was constructed with deliberate difficulty to synchronise with a film of the same piece, choreographed with the artist wading in the waters amongst the stumps of the ancient trees. Sub-currents of bodily connection, deep time, loss and conflicting energies are tangled with the complexity of our efforts to be “in synch” with the natural world.

.

Multiple disciplines, forms of energy and Irish locations also feature in the intimate sample of images and documents offered by Reiko Goto & Tim Collins from their project HAKOTO / Portach / Bog. What looks like a combination of scientific experiment and ethnographic history is actually an affecting act of sensitive and respectful listening to the troubled breathing of an aged ecosystem.

.

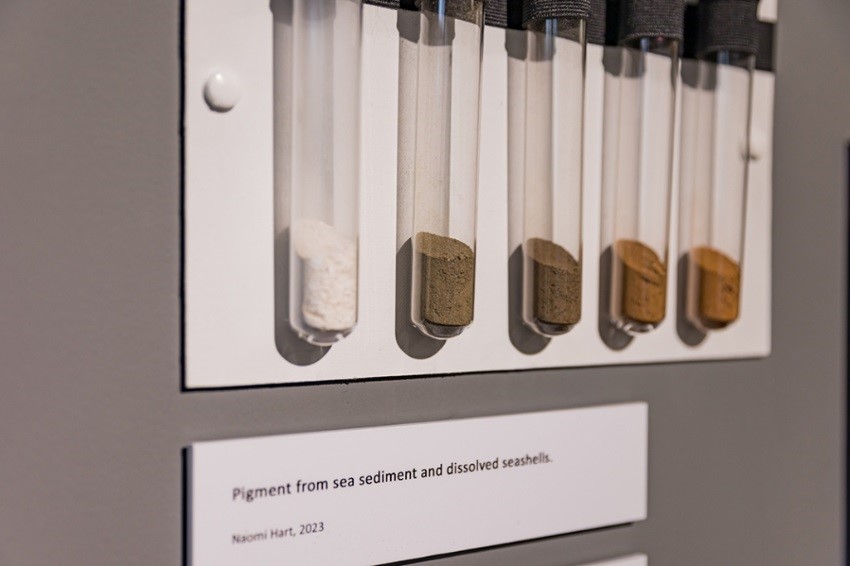

Naomi Hart is one of several artists providing work that results from partnering with scientists, in this case a residency with marine biologists and oceanographers studying “the world’s largest carbon sink” in sediments on the sea floor. Hart’s three portraits of benthic creatures are painted with seawater mixed with collected muds and dissolved shell pigments, samples of which are displayed beneath, in laboratory tubes. The collaboration with scientists gave the artist entry to the research environment and an understanding of the ecological context; and we are perhaps left wondering what new perceptions and dialogues then followed the production of the resulting art.

.

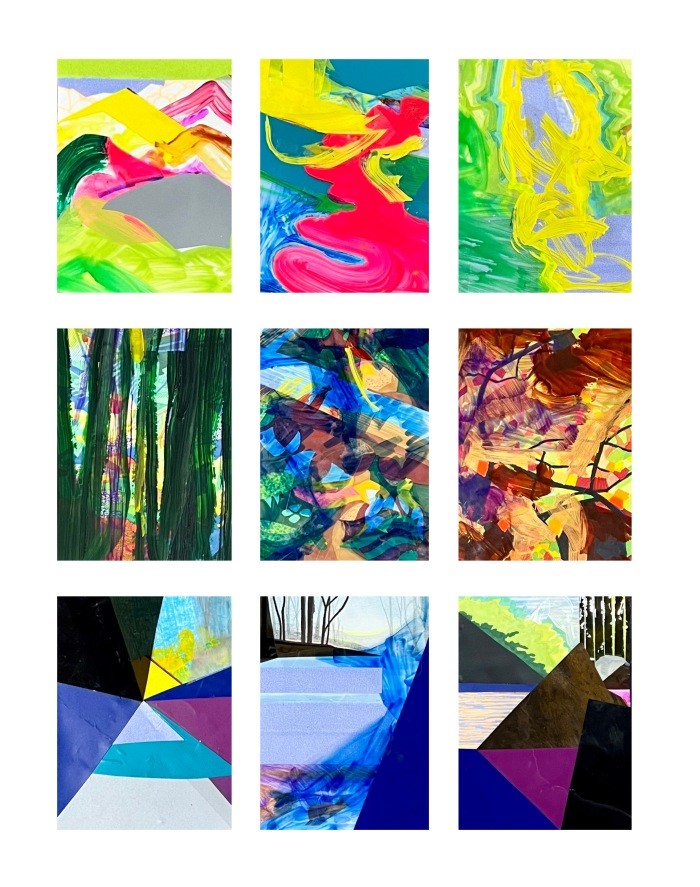

Such a mutual exchange is perhaps more apparent in the collaboration between Rita Leduc and ecologist Rich Blundell, which led to the vivid group of collage paintings she exhibits here as How the Light Gets Out. The pair have a shared fascination with the behaviour of light in and around the famed Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire, USA. Their joint explorations are lyrical and contemplative rather than technical, focusing on the properties of light in the forest as a way of “reconnecting with natural intelligence” in our present time of crisis. The paintings, on perspex, have their own luminous vibrancy, and they reflect a glint of human hopefulness that comes through several of the other works in the exhibition.

.

Lyrical and personal impressions and expressions are well represented here, and there are fewer works born from social engagement projects. One exception is Daksha Patel’s Tree Against Hunger. Patel worked with refugees and asylum seekers in Manchester, sharing food as a starting point for explorations of plants, farming, climate change, heritage, sense of belonging and displacement. Crop resilience and food security become metaphors as well as practical necessities for society’s adaptation to environmental upheaval. Patel’s large, exuberant print of the flower and fruit of the Ethiopian “tree against hunger” (Ensete ventricosum) lists the local names by which the species is embedded in ancestral knowledge concerning its productive properties. It was one of three works by the artist that featured in an exhibition in Manchester Museum in 2024, where her workshop participants and their families were given tours in their own languages.

Mention should be made of the community engagement elements that also lie behind Helen Cann’s A Moss of Many Layers (her hand-drawn narrative map of Bolton Fell Moss nature reserve in Cumbria), and Anne Waggot Knott’s Small Water (an installation that draws attention to the preciousness of water).

Variety continues further with the inclusion of sculptural works. The intricate steam-bent ash of Charlie Whinney’s swirling Life Swims Uphill is his musing on order and disorder in the biosphere. However abstract, it seems to prompt an inner recognition of phenomena that hold true at sub-atomic and cosmic levels, and everywhere in between. Sam Gare’s Keening, Song of the Stranding, also in pale wood, has a poignancy in suggesting (her words) “the negative space where life once was”; while Edwina Fitzpatrick’s wall-mounted papercut woodland has us looking upward at a mycorrhizal network, instead of its usual relegation beneath our feet. Small shifts of perspective like this can be the catalyst for important reappraisals.

Then for further self-examination, approach the unassuming white-framed square of What is this gold? by Kate Brundrett. Not typical of her work in general, this ostensibly simplest of the works in the show (a panel of earthy bronze colour, and some accompanying words) exerts a potent intrigue about the nature of material, the business of putting it in a frame as spectacle, warped systems of value, and subjectivity of response (what do we bring? what does it bring?). The strangely magnetic effect of this piece is not easy to explain.

Enriching all the above we have other contributions covering birdsong (Mike Collier), tree and flower drawings and prints (Richard Bavin, Richard Gilbert, Camilla Nelson, Lance Oditt), soil erosion and techno-fixes (Becky Nunes), ice (Anna Sharpe), the solar day (Simon Hitchens), wildfires (Luke Walker), bog puppets (Kate Foster), stories in textiles (Siobhan McLaughlin), films, music and more.

.

To look for commonalities and unifying threads in such a cornucopia may be a false quest. There is nonetheless an atmosphere of shared struggle for sense-making and meaning-making (as distinct from efforts at “place-making” or “community-making”). An emphasis on investigating materiality is prevalent; which in the rise of the digital age is not insignificant. Somatic and personal connections also come across strongly, though social engagement projects feature less.

There is perhaps a key paradox at the heart of this exhibition. Many of the artists remind us of (and demonstrate) the critical importance of slow organic understandings, and the patient “deep noticing” that puts us in more intelligent relation to the world we inhabit. This is a valuable learning curve. At the same time, the defining context here is a matter of “urgency” (the climate and ecological crisis). Few of the works in fact speak to this time-pressure component, despite its centrality in the title of the show; and any reference to “urgency” was largely missing from the presentations at the opening event. How we square this circle, between slow depth of appreciation on the one hand, and immediate crisis response on the other, may therefore remain a challenge for us all.

The visitor to this exhibition nevertheless comes away with a head full of lasting images of aesthetic diversity, and thoughts to reflect upon – both slowly and urgently.

There is a strand of positivity and constructive analysis flavouring the presentation overall, which has an extreme sincerity of intent and execution. There is no intention to shock. Some however might argue that we need a shock. They might look for a “harder edge” to the impact being sought by artist responses to the show’s brief, and a starker portrayal of the scale of what hangs in the balance – the social injustices, crimes of ecocide, power-politics and environmental systems collapse that lie behind the somewhat gentler stories here.

But – is it the job of artists to do this? The artists are a conduit. Our question should perhaps more correctly ask what should the art be doing here – and that implicates us all, as participants in it, respondents to it, and perhaps contributors to it. Perhaps it’s our job to see what’s “here, now”, and cultivate the greater “urgency” that may have been lacking in the world thus far.

Exhibiting artists:

Ali Foxon; Anna Sharpe; Anne Waggot Knott; Becky Nunes; Bryony Ella; Camilla Nelson; Charlie Whinney; Colin Riley; Collins + Goto; Daksha Patel; Dave Camlin; David Haley; Debbie Yare; Edwina fitzPatrick; Helen Cann; Juliet Klottrup; Jools Gilson; Kate Brundrett; Kate Foster; Lance Oditt; Luke M Walker; Mike Collier; Naomi Hart; Richard Bavin; Richard Gilbert; Rita Leduc; Sam Gare; Sarah Smout; Simon Hitchens; Siobhan McLaughlin; somewhere nowhere (Harriet Fraser and Rob Fraser).

.

See Here Now – Art in a Time of Urgency can be experienced at the visitor centre, Grizedale Forest (postcode LA22 0QJ), until 8 June 2025. Opening times: 10am to 4pm (admission free). For directions and access details see https://www.forestryengland.uk/grizedale .

More information about the exhibition can be found here: https://theplacecollective.org/see-here-now-exhibition/ , and for details of the PLACE Collective see: https://theplacecollective.org/home-2/ .

Dave Pritchard is an independent consultant in environment, culture, heritage and the arts; based in the UK and working internationally.

Leave a comment